How to use ChatGPT for science communication

I’m a bit late to ChatGPT, the artificial intelligence chatbot from OpenAi that’s been making waves since it hit the headlines late last year.

For the past few months, I haven’t been able to open my LinkedIn feed without finding another post about how ChatGPT is changing the game for bloggers, marketers, social media specialists and a range of others in the business of knowledge production.

I’m interested in ChatGPT’s potential for science communication. So, I decided to take the plunge, sign up for ChatGPT, and start learning about what it can (and can’t) do.

In this post, I highlight a few ways science communicators can use ChatGPT to assist with science communication. I also include an important section on why you can’t trust the references ChatGPT gives for the information it cites and what this means for how you use ChatGPT.

To start, let’s look at four ways to use ChatGPT for science communication.

(*Note: the examples below were generated with the March 14, 2023, version of ChatGPT).

Use ChatGPT to cut jargon and simplify language

One of the main tasks of a science communicator is to simplify complex, field-specific language and make it accessible to non-specialists (Read more about Carl Sagan’s advice on the importance of keeping it simple).

ChatGPT can help with this. And does so at an incredible pace.

I asked ChatGPT to simplify the first key message from the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change AR6 Synthesis Report. These climate change reports are notoriously dense and jargon-heavy. Having recently worked on a large climate change project, I’ve been neck-deep in jargon!

ChatGPT returned a paragraph that is clear and less unwieldy than the original. I would do more work on this and fine-tune it for the intended target audience. But it’s a good start.

Use ChatGPT to help explain scientific concepts (and limit the wordcount)

Science communicators often grapple with how to explain complex scientific concepts in a way that non-scientists can understand. ChatGPT can help with this.

I asked ChatGPT to explain ocean acidification as if it were speaking to someone with a high school education.

The first answer it gave me was way too wordy. So, I asked it to summarize its lengthy first reply into 100 words. This is what it came up with (clocking in at 99 words):

ChatGPT’s response was clear. But it includes the jargon term “cascading effects.” So, I asked it to explain what this means and it provided a useful explanation.

Use ChatGPT to brainstorm ideas for blog posts

I have seen numerous LinkedIn posts about using ChatGPT for blogs. A helpful way to use it is to brainstorm ideas for potential posts on a particular topic. This can help you identify angles that you might not have considered.

For example, I asked ChatGPT to give me five ideas for a blog post on one of my favourite topics: Why science communication should be part of the curriculum for students studying science at university.

It came back with five ideas, each with different angles. One looked at the role of science communication in public policy; another focused on the value of science communication for future scientists.

Once you’ve decided on a blog topic, you can take it a step further and get ChatGPT to generate an outline for your blog post.

I see this process as akin to brainstorming because it involves bouncing ideas and exploring different angles for writing. I wouldn’t recommend getting ChatGPT to write an entire post, or just blindly following the first outline it spits out.

Use ChatGPT to generate ideas for talking points for different target audiences

In the science communication course I co-instruct, I always stress the importance of tailoring scientific information for different target audiences. The more you understand about your target audience and what they care about, and the more you can speak to their concerns, the more effective you can be with your science communication.

With the right prompts, you can use ChatGPT to generate ideas for what to focus on when engaging with different target audiences.

The more specific you can be about the target audience the better.

I asked ChatGPT to give me pointers on what topics to cover when speaking about climate change to farmers in the Karoo (a semi-desert region in South Africa), a South African mining industry group, and a non-governmental youth organisation with the aim of inspiring young people to take climate action.

In each case, it gave me four to six issues to discuss. Most of them helpful.

For the farmers, one of ChatGPT’s suggestions was water scarcity: “The Karoo is a semi-arid region that already faces water scarcity. You could discuss how climate change is likely to exacerbate this problem, with more frequent droughts and changes in precipitation patterns. You could also discuss strategies for adapting to water scarcity, such as water-efficient irrigation and rainwater harvesting.”

For the mining industry, one of the topics it suggested was carbon pricing and regulation: “Carbon pricing and regulation are likely to play an increasing role in shaping the global economy and the mining industry. You could discuss the need for the industry to prepare for these changes, and strategies for minimizing the costs and risks associated with carbon pricing and regulation.”

ChatGPT provides a starting point

With all of the examples mentioned above, ChatGPT can be useful as a starting point. But it doesn’t replace the work of a science communicator.

When using ChatGPT, it’s important to parse through the suggestions its generates and decide which will be most appropriate and effective for your target audience and communication strategy. It’s also crucial to fact check its responses (more on that later).

In science communication there is also the vital issue of human connection. That can involve speaking with different people in your target audience to properly understand their concerns, hopes and dreams, or sharing your own vulnerability in a presentation. That’s not something you can outsource to ChatGPT.

One thing ChatGPT can’t do is back up its claims with credible sources

The original subtitle for this section was How ChatGPT is already being used for science communication. But that exuberant line changed due to reasons I’ll outline below.

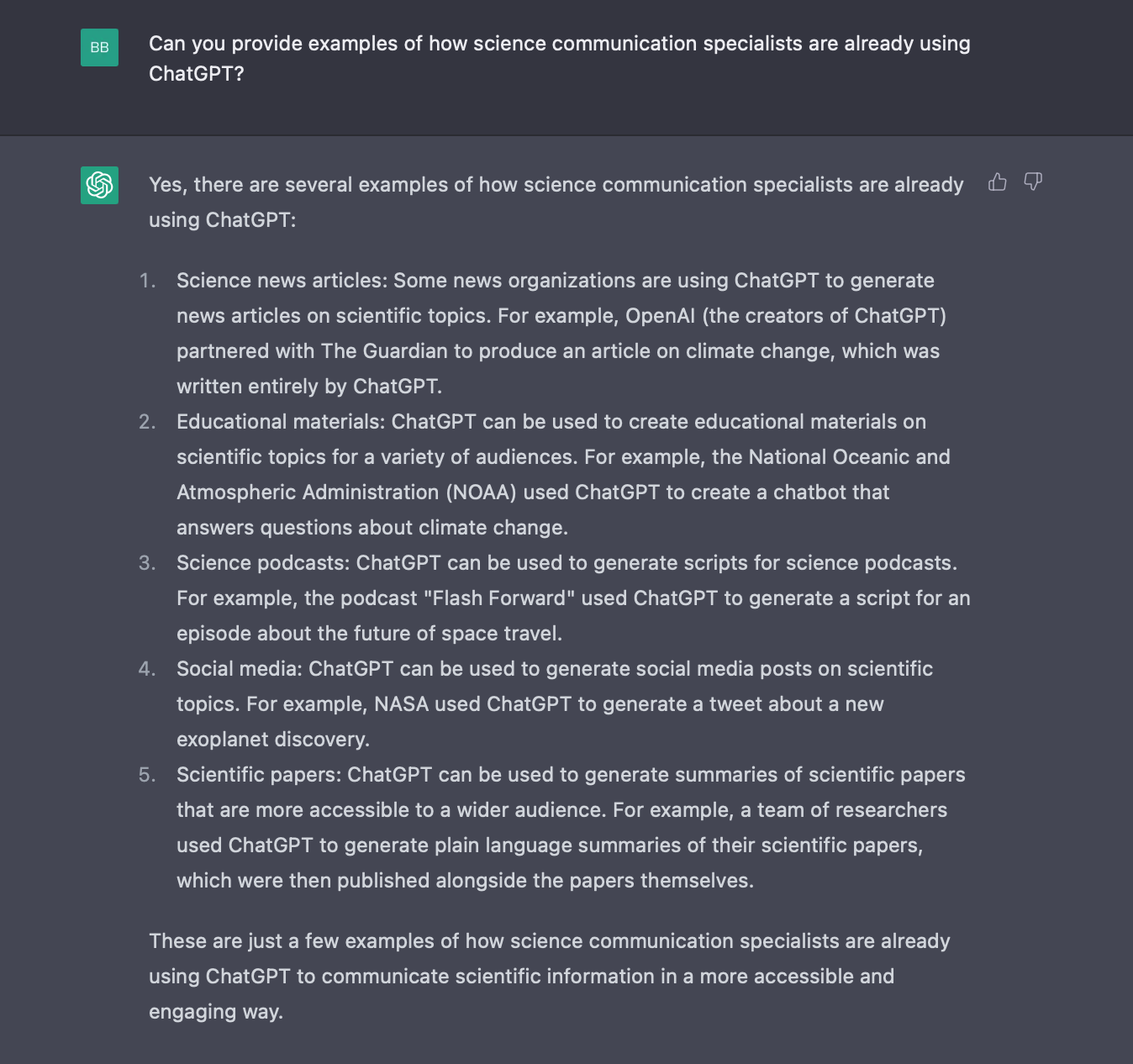

When researching for this post, I asked ChatGPT to give me examples of how science communication specialists are already using ChatGPT. It quickly knocked out five impressive looking examples.

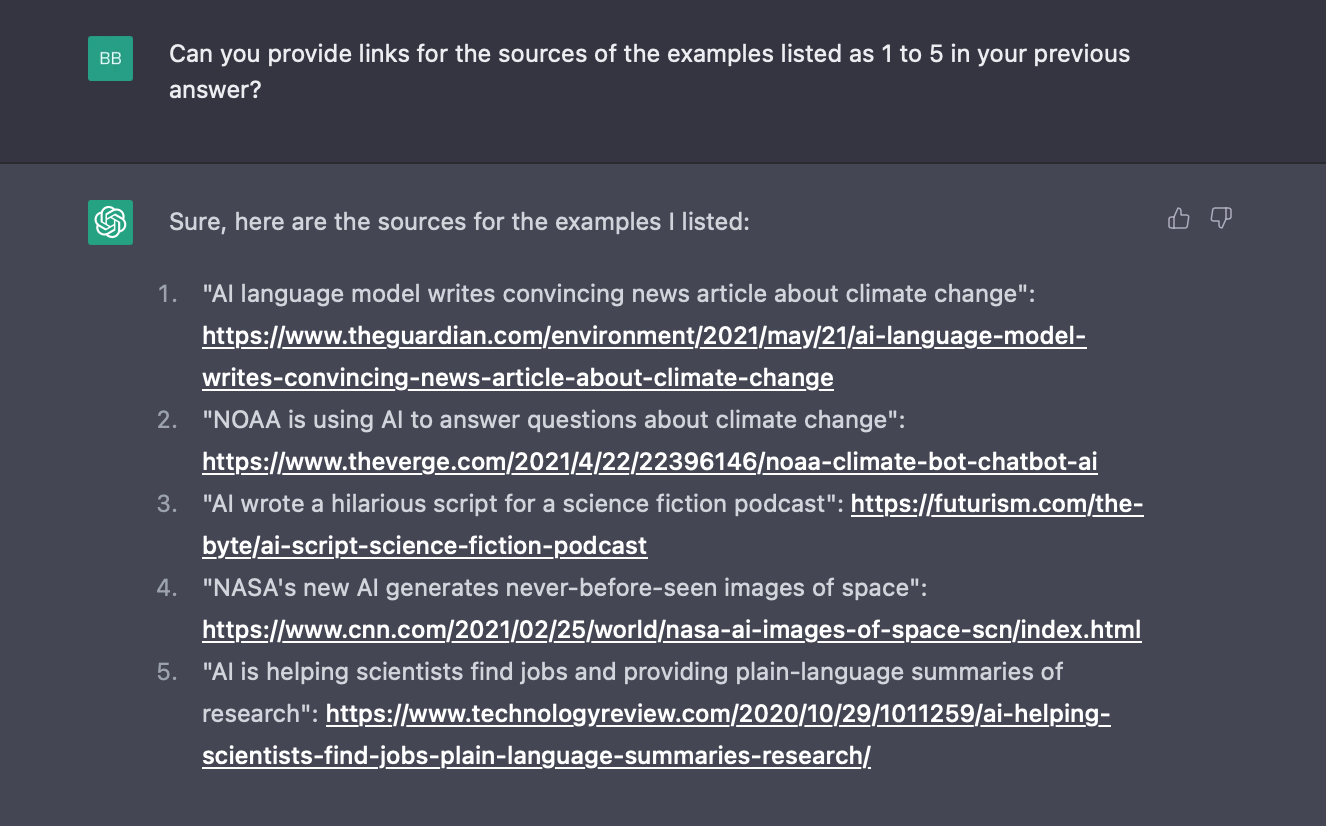

To check the veracity of ChatGPT’s claims, I asked the chatbot to provide links for the sources of these examples. It did so in characteristically speedy fashion.

I was initially (and naively) excited about this. Since ChatGPT does not give citations for the answers it provides this seemed like a good solution: ask the bot to back up its claims with published articles.

There was just one problem: none of these links exist! Each took me to a broken URL page or a “sorry this page can’t be found” (404 error) message.

I gave ChatGPT the benefit of the doubt and tried finding the articles with Google search. Again, dead end.

Turns out, ChatGPT is known for fabricating citations (as well as spreading falsehoods, known as “hallucinations.”)

Mathew Hillier, an e-assessment in higher education specialist, has written an excellent deep dive on this issue for Teche (Macquarie University’s Learning and Teaching community blog). In a test, Hillier found that five of six references ChatGPT provided were fake.

Blog posts by Duke University and The Oxford Review also highlight how ChatGPT concocts academic references.

Why does ChatGPT do this? As Hillier explains:

“ChatGPT is a ‘large language model’ designed to output human-like text based on the context of the user’s prompt. It uses a statistical model to guess, based on probability, the next word, sentence and paragraph to match the context provided by the user.

The size of the source data for the language model is such that ‘compression’ was necessary and this resulted in a loss of fidelity in the final statistical model. This means that even if truthful statements were present in the original data, the ‘lossiness’ in the model produces a ‘fuzziness’ that results in the model instead producing the most ‘plausible’ statement. In short, the model has no ability to evaluate if the output it is producing equates to a truthful statement or not.”

(For a fuller explanation, read Hillier’s post at Teche).

The fact that ChatGPT spins together credible sounding references that don’t exist points to the need (and duty) of science communicators (and anyone else using ChatGPT) to verify the information ChatGPT provides.

Science communicators need to pay careful attention here, cross-checking to ensure that facts, figures and claims from ChatGPT are grounded in credible research.

A tool to approach with curiosity

I won’t lie: discovering that all the references ChatGPT gave me were not real dampened my enthusiasm about the bot. But after reading more about this, I understand that providing citations is not something ChatGPT is designed to do.

I remain curious about ChatGPT and its applications for science communicators. Generative AI is developing at a rapid pace. It’s now part of the communication landscape, for better or worse. Science communicators (and communications specialists in general) need to know how to use this technology, and clearly understand its potential and limitations.

I still have much to learn about ChatGPT. I’m particularly interested in how to pair its obvious benefits with improved methods for making sure that the information it provides is verified and properly referenced.

From my brief experience so far, I feel there is value in using ChatGPT to bounce ideas and explore topics I might not yet know a lot about. And I still find it mind-blowing to interact with this technology. It feels like such a leap forward from the digital tools I’m used to.

Sometimes, it feels like we’re living in the future. As a science communicator, I don’t want to get left behind.

Are you using ChatGPT for science communication? How so? Let me know in the comments.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like:

Brendon Bosworth is a science communication trainer and the principal consultant at Human Element Communications.